From the public reading of the diploma report January 2009

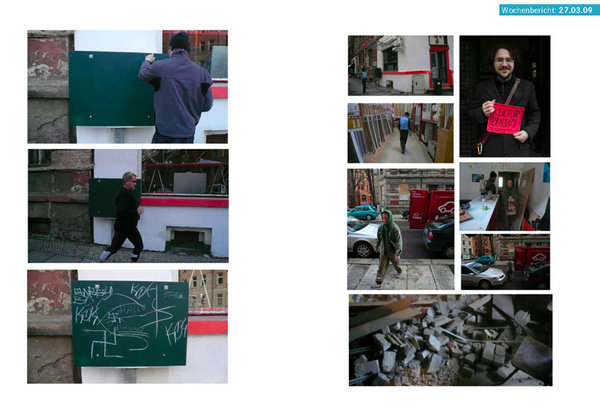

Visual art is a language through which the relationship between man and the world can be subjectively reinterpreted time and again. It can also become a tool that can be used to bring about intuitive or targeted changes in society. When graduate student Matthias Ritzmann set out a few months ago to find atmospheric backdrops in Glaucha for an aesthetically sophisticated photography project, he wanted to make use of the traces of decay in people and space in order to stage an authentic plot for a crime story. At that time, no one had any idea what he had achieved to this day with his camera, with a lot of courage, creativity and enterprise for the neighborhood and the people living there, and not least for himself.

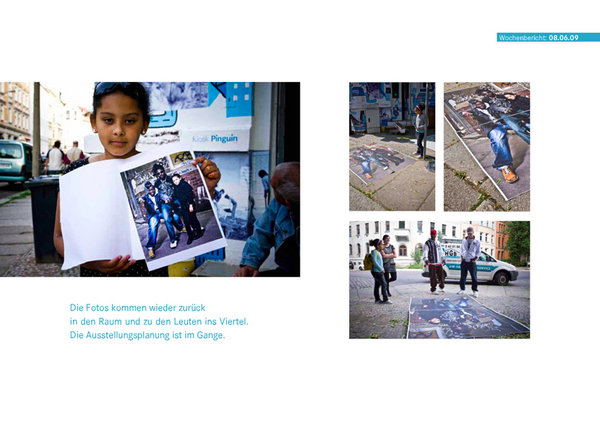

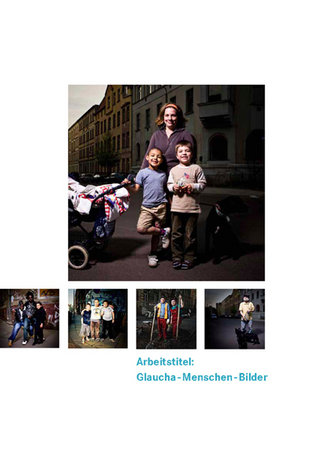

“The future lives in Glaucha” was the headline of the Bild newspaper a few days ago, a catalyst and manipulator of opinions that only deal with art projects to the extent that people’s instinctive fears, longings and hopes emerge from them. “Glauchaers smile for Glauchaers” is the headline of the Saale Kurier, picking up on a mood that spread in the neighborhood around the starting point of his work, the Pinguin kiosk, after the exhibition of Matthias Ritzmann’s pictures. “We all knew each other here and now it’s like dead. My goodness! A lot has to change here!” says an old woman who wakes up for a moment from her backward-looking nostalgic contemplation of the past and suddenly sees herself as an important part of a necessary process of change. “I like living here because it’s a colorful mix. I wouldn’t change so much,” says a young man who presumably moved to Glaucha because it’s cheap and central and because something has begun that is now coming to light. A new class of people is appropriating a central district of Halle, which has lost a large part of its traditional population in the process of shrinkage. The remaining people are often the ones who couldn’t leave, who feel left behind, sidelined, which is why they shy away from contact with the new residents, who are culturally different, younger, stranger, more hopeful and therefore also more alive. But who can find a language that everyone understands, who can create connections between people whose lives are fundamentally different, native Halle residents and foreigners thrown in by bureaucratic distribution mechanisms, old and young, students and the long-term unemployed, workers and intellectuals, if not the image that shows: “We all have one thing in common, we live and live here together, we are Glaucha.”

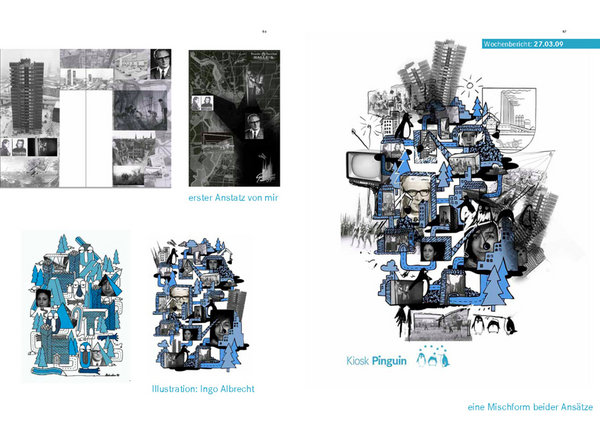

“In the beginning was the word”, says a profound reflection on the human desire for knowledge, but for Matthias Ritzmann it all began with the images, which were his linguistic tool throughout the entire process, as well as making the concept, form and content of his thesis visible to everyone in the end. Whenever Matthias lacked the words to explain his thoughts and ideas, which was quite often the case during the diploma period, he brought me pictures, strong pictures, which he combined into series to express his ideas. And I often showed him pictures when I didn’t have the words or felt they were too vague to convey my responses to his work or to give him suggestions.

The pictorial space is his original linguistic and creative space, where he allows layers of space to emerge or disappear with precision, where he detects, creates and shapes formal relationships by playing with atmospheres of color and light and constantly revealing new perspectives between observer, object and light source. The view from below of the people in his pictures simultaneously elevates them and turns them into everyday heroes, whose character transcends their outward appearance and comes to the fore against the backdrop of the neighborhood. “Who am I actually here and now?” the people in the pictures asked themselves at the public exhibition in the neighborhood, just as the other viewers were encouraged or sometimes almost forced by the pictures to reflect on their own life situation. His pictures provoke, flatter, beguile or confuse, which is further enhanced by the larger-than-life presence of the people depicted, who stand together in a circle in the middle of which a fruitful dialog develops throughout the day of the exhibition. In this way, they are both a trigger and a component of a communication process that one hopes for in vain in many a gallery. It is felt, thought and spoken through the pictures, not about the author, but about what they reveal for each individual viewer.

Art concerns us all! From the beginnings of cultural history to the present day, it has had the power to bring about social change, just as it has always transformed the artist’s own world view and way of acting. The focus of Matthias Ritzmann’s work has changed over the course of his diploma thesis. It has matured through the artistic and creative dialog with the local people, with his friends in the Pinguin kiosk and with the unexpectedly strong emotional and substantive reaction of the public to his pictures, has gained even more personality and strength and also shows him a good and meaningful creative path into his own artistic and creative practice after his studies.

In order to pay tribute to his dedicated and exceptionally fruitful work, I would have preferred to give the graduate a very personal picture today rather than these words. But doesn’t every one of our words ultimately serve to create an image in the imagination of the listener, which acquires its spatiality and reality through the power of the associations evoked in each case? Images and words develop their effect in time and space, and so Matthias Ritzmann’s work will have consequences for himself and many viewers that go far beyond the present day.