Denkwerk artwork

Lecture January 04, 2014, 18:30 Berlin, Denkerei

Preliminary remark

In the sense of the cultural theory of the “open work of art” developed by Umberto Eco, cultural artifacts are never finished, because they only find their completion at the moment of their perception.[1] The aesthetic perspective on the object of art is therefore completely different from the historical or economic perspective. In the “Origin of the Work of Art”, Heidegger speaks of “putting truth into the work“, whereby the work becomes the site of a mediation event and incites people to search for truth.[2 ] The concept of the openness of works of art can be extended to all products of human cultural creation that become the object of human learning both through the act of their creation and through their perception and use. The principle of their creation in the production process and recreation in the reception process ensures that people take up the ideas underlying the creation in the sense of an offer of discourse, that they begin to ask their own questions and search for their own answers. The productive learning process that an object of human activity triggers in the brain of its creator or recipient, the impulse that is passed on, which generates inspiration, creativity and motivation and initiates new actions, makes the result of the work expended stand out from the multitude of traces that a person leaves behind in their environment.

The concept of a work

Each work (ahd. werka – Work) represents the result of a productive activity and thus forms the material counterpart or the ideal expression of the intellectual or manual work performed for this purpose. The benefit of a work is not limited to the possibilities of its ideal and material utilization, but always includes the educational process of its author. Through the production process, verbal skills recede into the background, while the function of sensory perception moves to the center of the productive debate, which, like language, functions as an instrument of knowledge and understanding as well as problem-solving and mediation. The practices necessary for the production of works also demand and develop knowledge, skills and abilities of the content and methods, tools and materials, media and effects relevant to the creation process. The formation of the mental and material material into a work takes place through the visualization, embodiment and spatialization of the ideas introduced into the work process or generated from it (gr. idea – idea, opinion, appearance, archetype). To produce a work of art, a person needs a driving force or a motive (lat. motus – movement, drive), which comprises the sum of the motives that move him to the work process or drive him to its end.

Every work remains dependent on the will and intention of its producer or intellectual author, insofar as it conveys the conditions and intentions of its production to users, listeners and viewers in an unambiguous manner and prescribes its use. On the other hand, a work only achieves independence through its ambiguity, as this allows it to become the subject of new intellectual and practical discussions in the context of its perception. The production of a work is innovative (lat. innovare – innovate) when it contributes to the renewal of the thoughts and practices of its creator. However, a work only becomes innovative when it contributes to the renewal of society, i.e. when it has an impact on the present of its reception. In terms of the power of change, it makes no difference whether works tell a coherent or incoherent story, make use of abstract or concrete formal elements, permit unambiguous or ambiguous readings, have been completed or remain unfinished in the sense of a draft or a sketch of an idea.

Every creator lives and has an impact on future societies through his or her work, even if the artificial genes passed on do not create life, but culture. The ambivalent character of the work puts its creator in a quandary, as he will be present and absent in it at the same time, as in the continuation of his physical descendants. James Joyce deals with this in his last novel, which he initially published under the title “Work in Progress“. This is based on the Irish ballad “Finnegan’s Wake”, which deals with the death of master builder Tim Finnegan, who is awakened by the violent celebration of his own funeral.[3 ] Each work forms the occasion for a chain of new perceptions, thoughts and actions within societies over which the author no longer has any power, even if he is present in them in a very personal way.

The work as a source of knowledge

This powerlessness and loss of control over the conditions of reception distinguishes the work form from personal conversation, from a lively discourse in which the author can offer explanations, react to misunderstandings, admit mistakes or record thoughts. This silent skill of the work already had a disturbing effect when outstanding thinkers of Greek antiquity such as Socrates decided to reject the writing, visualization or materialization of knowledge more than 2,400 years ago.

Plato also regarded textual and pictorial works as secondary sources of personally acquired knowledge and self-made experiences. In his view, an idea possesses authenticity and credibility neither through the work nor through the presence of the author, but solely through the way in which it is conveyed.

The art is therefore not in imitation (lat. imitatio – imitation, replica) of ideas through the work, but in the persuasion of the audience through the personality of the author in a question and answer process. Plato understands the art of oratory(ancient Greek rhetorike, techne) as the guidance of the soul, which in his view can only be achieved in the form of a personal dialog (Old Greek diálogos – conversation’ talk) can be successful. For him, on the other hand, works are monologic forms of expression through which the author can instruct his listeners or viewers, but cannot bring about knowledge, which he equates with self-knowledge. Plato criticizes the nature of the work, which is an indirect form of transmission and does not allow the author to address the audience directly. Where it is not possible to react to a lack of knowledge, bias or simply false expectations, knowledge is left to chance. The aim of imparting knowledge, passing on experience and creating insight is lost sight of, the work becomes an end in itself.

Dialogue between Socrates and Phaidros

[4]

“SOCRATES: He, then, who believes that there is an art in writings, and again, who assumes it as if something clear and reliable could be taken from letters, will probably be simple-minded enough and indeed not know the truth of Ammon, believing that written speeches are something more than an aid to memory for those who already know what the writing is about.

PHAIDROS: Very true!

SOCRATES: For writing has this defect, O Phaedrus, and in this it is like painting. For the works of these, too, stand there as if alive, but if you ask them anything, they remain very nobly silent. In the same way the speeches, you might think they speak as if they understood something, but if you ask about something of what is said with the intention of instructing you, they always indicate only one and the same thing. And when it is once written, every speech goes about in all places, equally among those who understand it and among those for whom it does not belong, and does not understand to whom it should speak and to whom it should not. And if she is insulted and unfairly abused, she always needs her father’s help, because she is neither able to protect nor help herself.”

Plato, like his teacher Socrates, did not dispense with the written form, but he circumvented the problems of monologic narrative forms by inventing the “Platonic dialog” named after him. With the help of the dialog form, he brings Socrates’ speeches into work form, thereby removing one of the most influential sources of human thought from oblivion. The timeless topicality and impact of his discourses, preserved solely through the work form, can be traced back through cultural history.

It is not mortal brains, but the lasting effects of culture that shape the memory of mankind, a thesis that is not meant metaphorically, as it can be proven by neurobiological correlations. Neuropsychologist Karl Gegenfurtner describes the environment as the “external image storage” of human memory, whose networking and processing structures ensure the connectivity and legibility of external information.[5] Once set into the work, the author’s outsourced message is conveyed to readers, listeners and observers in the context of their respective perceptual situation, whereby the ideas on which the draft is based are actualized all by themselves.

The Platonic dialog form challenges the reader again and again to ask himself all the questions and at the same time enables him to understand the train of thought presented, to criticize it and to form his own opinion. The disclosure of the question in the dialog form also contains the core of scientificity, as verification and falsification of the theses presented becomes possible. In the dialog form, it also remains open whether further answers to the questions expressed are possible, whereby the problem is passed on to the recipient.

Nevertheless, Plato does not refrain from instructing his readers in his work, as all the questions posed are answered and at the same time it is revealed that the dialog form is used as a didactic means of developing the problem. By setting up the discourse, an exchange of experiences across society and generations is stimulated, as long as it inspires people to think and act in a reciprocal way. Works that exist before history not only convey to the recipient the discourse of their time of origin, but also provide an occasion and model for their actualization in the context of the present. A timeless work of thought communicates not only the content, but also the joy of discursive thinking, in which the search for the convincing argument incites the recipient to conduct his own research, infects or infects him to shape the discourse by means of his own creations in order to keep its productive power alive. In this sense, works form the cultural seed, the genetic material separate from the body, which keeps the discourse on determining the position of human existence in the environment open, versatile and alive from the beginning of cultural evolution to the present day.

The creation process as a source of knowledge

Whereas Plato’s form was the embossing material of an eternal idea existing in it in the form of an image, Aristotle’s inner spiritual form, rooted in the soul of the author, is only realized through the shaping of the sensual material. For him, a work is more than the depiction or imitation of a universal principle, as the design or thought is realized in the concrete form and thus becomes accessible to thought. The manufacturing process becomes a creative process of perception of the particular, the craft becomes a sensual form of knowledge. While the work of depiction seeks to achieve maximum similarity to preconceived forms of thought and perception through masterly craftsmanship, the focus of the work of allegory shifts to the aesthetic form of knowledge, which is on a par with the intellectual work of science.

The general in the particular is revealed to the observer through rational thinking(cogitatio). Gaining knowledge through sensory perception(cognitio sensitiva), on the other hand, consists of recognizing the particular in its particularity.[6 ] In his rhetoric, Aristotle referred to the active role of the listener, who should be enabled by the speaker to think and judge independently about the past and the future.[7 ] The creative quality of a work, regardless of whether it is a word or an image, is thus demonstrated by the effects it has on the recipient, who is thus given the freedom and responsibility to form his or her own judgment.

The act of creation is not only craftsmanship, but also the art of teaching or didactics(didaskein – to teach), whereby quality criteria such as clarity, interest, enthusiasm, awe and persuasiveness or even readability, comprehensibility and sustainability gain in importance.

Not only what a work conveys and what it is used for, but also how it conveys its message and how it is used becomes a central component of the genesis of the work. The question of “how” opens up an ongoing debate about human perception and its role in thinking, imagining, representing and shaping reality. Aristotle’s insight into the nature of human perception was not implemented until 2000 years later, when Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten gave new impetus to the science of perception in his work Aesthetica in 1750.[8] This return of art and science to the roots of aesthetics (aisthetos – the perceptible) was possible because, with the beginning of the Enlightenment, the symbolically charged work of art, which stood far above the craft, emancipated itself from its function as a representative of state and religious claims to omnipotence and gradually regained the independent critical function that Aristotle once ascribed to it.

The emotional quality of image perception

However, as one of the most important theorists of the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas already followed Aristotle to the extent that, in contrast to Plato’s view, he did not define man and nature as images of eternal ideas or divine principles, but as their bodily and material realization. Man and nature thus become a perfect work of creation through which the divine spirit reveals itself in infinite diversity as the idea underlying all existence. The Church bears responsibility for the preservation and function of creation as God’s representative on earth, which gives it an unrestricted right to interpret God’s will, which it exercises through the power of interpretation and the sovereignty of representation of images and works of thought. The medieval role of the work of art as a mediator of absolute truth and divine will deliberately deprives the recipient of the freedom of independent knowledge and judgment, since criticism of the image is considered heresy (gr. Hairesis – Choice, Conviction) is perceived.

The revelation of the divine principle of creation calls for quiet reverence and devout inwardness. The authors of the works are not important, they remain in the background and are often not even handed down. The variance and richness of countless pictorial works convey to viewers, most of whom are illiterate, a ready-made, self-contained, irrefutable world view that represents the belief in one truth and makes independent thought superfluous.

The widespread illiteracy of the Middle Ages is continued in the realm of pictorial works, whose motifs are for the most part richly decorated metaphorical interpretations of the Bible and illustrate and confirm the truth of the spoken word in a vivid way. The Visual illiteracy, as criticized by Charles-Pierre Baudelaire and Walter Benjamin at the beginning of the age of film and photography, is the cause of human immaturity, which can only be overcome through cultural education.[9 ] Cultural education in the sense of the Enlightenment is not achieved through verbal and visual literacy alone, but requires the ability to engage in discourse in which independent thinking can emerge and develop. Cultural educational success is therefore not reflected in the quantity of memorized knowledge, nor in practicable manual skills or knowledge of methods, but solely in the quality of the discursive process of thinking and creating, the result of which manifests itself in the form of the work.

The restrictions on the content of medieval arts and crafts gave an enormous developmental boost to the examination of the manner of sensual perception, as the authors invested their creative energy in the design and persuasive power of the work form. The use of globally traded color pigments, dramatic lighting scenarios, fragile constructions, geometric forms, imaginative ornamentation, unusual perspectives, precious materials and complex processing techniques promotes the sublimation or spiritual exaltation of the pictorial object. Medieval artists such as Giotto, who lived at the turn of the 13. to the 14th century. was later appropriated as a pioneer of the Renaissance, although the inventions named for it all apply to the effect of the content, but never call it into question.

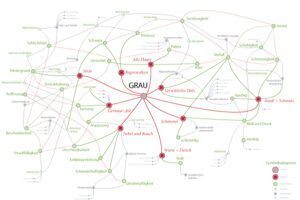

This makes it clear to what extent the content and formal genesis of each work reflects the social discourse of its time of origin, which in turn is the result of other discourses. The history of works can therefore not be reconstructed linearly and hierarchically, but far better in the rhizomatic form described by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their publication “A Thousand Plateaus”.[10] as an organizing structure for a contemporary model of knowledge and world description. The question of an order for the works of human culture has an epistemological dimension, as it applies to the process of knowledge that has become form, which can be depicted less in stylistic periods and encyclopaedias than in the rhizomatic hypertext structure of the Internet.

The theatrical staging of the space in the sense of a Gesamtkunstwerk as well as the targeted manipulation of the emotional mood change the mode of perception, a discovery of the Middle Ages that was first described in the sketchbooks and textbooks of Renaissance artists such as Leonardo da Vinci.[11] The significance of emotion and feeling for the perception of works of art has determined the debate on aesthetics right up to the neuroscience of the present day, which is why I would like to use Martin Heidegger’s term “mood of the work” to characterize the path.[12]the aspect of “beauty as atmosphere” put forward by Gernot Böhme[13] and the brain function model of “somatic markers” developed by Antonio Damasio[14] would like to pick out.

Aesthetic perception as a vivid form of cognition

The 17th century. was not only the birth of aesthetics, but above all the Age of Enlightenment, which, according to Immanuel Kant, ended the immaturity of man and at the same time imposed on him the obligation to think for himself. Kant made a clear distinction between intellectual cognition (noumena) and vivid cognition based on phenomena (phaenomena). The much-discussed basic aesthetic concepts of ugly and beautiful appeared to him as purely subjective modes of perception, relative and therefore secondary, since in his view the aesthetics of a work are primarily determined by the perception of its meaningfulness.

According to Kant, the primary method of aesthetic research therefore had to be the analysis of perception, an idea that was taken up in phenomenology and Gestalt theory and is now being expanded and confirmed by the neurosciences.[15] For the analysis of works, Kant’s considerations mean that people can arrive at a direct understanding of complexity by means of systematic contemplation. The functional analysis of the perception of wholes, which includes the perspective of the observer and the context of the observation situation, provides the observer not only with more, but also with completely different insights than the set of individual parts.

On the other hand, the work develops a model character in the process of creation, which makes it the object of aesthetic research, which is no longer only concerned with the object of observation itself, but also with the insights gained into the nature of one’s own existence in the environment. The human mind does not produce knowledge independently of the way it is in the world, but on the basis of its views, which is why the works of nature are the only original source of truth. The works of culture, on the other hand, are not original sources of truth, but models of knowledge by means of which the perception of truth in the context of its time of discovery becomes conceivable, representable, communicable and questionable. A historical review of the genesis of the work reveals not only the changes in truths, but also the changes in ideas of reality, which at the same time reflect the changes in the cognitive abilities of people and societies to perceive themselves and their environment.

The transformative power of images

For reasons of time, I will limit myself in the following to a consideration of the function of pictorial works, which, like works of music or other forms of human cognition, can be works of art and thought, but often also fulfill such everyday purposes that the thought and artistry expended in their production must be ignored in order to preserve the concepts.

While a work of thought emerges from the successive process of linking words and moves readers and listeners to construct meaning, a work of image is given immediately in the simultaneous mode of viewing. Nevertheless, works of art are also revealed through the successive perception of individual significant elements in the field of vision, whereby the movements of the gaze also mark the process of cognition, while the whole is always in front of the observer’s eyes. The context of the whole is revealed through cross-references between the significant elements of the composition. Conventional arrangements increase the legibility of the idea and enable the observer to analytically reconstruct the creator’s intentions and working methods. Unconventional arrangements, on the other hand, generate ambiguous codes and encourage a variety of imaginative interpretations, which is why the observer must become creative through recreation and can arrive at completely new perceptions and insights.

Strong breaks with culturally grown systems of rules revolutionize the established conventions of perception of entire societies, which is why avant-garde pioneers are always needed who not only address uncomfortable questions through their works, but also question systemic functions. The unconventional approach to the production of pictorial works appears banal or annoying when observers do not feel addressed, do not find a new interpretation or perceive forms of representation as coercion that instrumentalize taboo-breaking for the mere purpose of attracting attention. When a breach of taboo changes society and when it is superfluous can usually only be decided with the benefit of hindsight, which is why there is always a need for courageous visual works that break with conventions of perception and accept the risk of failure. Revolutions in the perception of reality can be characterized by the unpredictability, uncontrollability and power of change of system-critical images, which, even without words, always demand more freedom and an expansion of social discourse.

On the other hand,the work form is dissolved when, as in happenings and new music, the shaping of the work is largely left to the performers, whereby authorship is preserved by limiting the possibilities of interpretation. The so-called aleatory (lat. alea – Cube) Concepts popularized by composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen or John Cage elevate chance to a theme and experiment with the performer’s ability to improvise.

The form of the work is always a means to an end, which is why improvised work forms are powerful, where creativity in interpretation becomes the central theme of creation. The completion of pictorial works by the creator can impair the legibility of the idea, which is why sketches, working models or spontaneous demonstrations often appear more powerful, inspiring and clearer than finished forms. Today, improvisation is an accepted form of work in its own right, which has also changed the aesthetic perception of spontaneous, infantile or autistic pictorial expressions.

From the epistemological order of pictorial works to the history of ideas

Human perception develops against the background of cultural education, which is why works of art evoke a wide range of interpretations, interpretations and emotional reactions that challenge judgments between approval and rejection. The interests of individuals and societies result in different benchmarks for the success of visual works. This is the cause of the rupture in the field of producers of pictorial works, some of whom serve the expectations of target groups and markets, which today guides almost all craftsmen, most designers and many artists, who act in a targeted manner out of the self-image of their professional groups and for reasons of securing their livelihood. Others, however, declare the creation process to be a open, independent search in the spirit of the Enlightenmentin which they ask their own questions, orient themselves towards their own interests, set their own goals, transcend their own boundaries, but also subordinate their own ego and prosperity to the will and development of the work, and experience conflicts, crises of meaning and final Failure risk.

According to the view already expressed by Samuel Beckett, “To be an artist is to fail“[16] it does not matter whether an artist fails with his work, since both the achievement and the failure of the intentions underlying the act of creation are irrelevant aspects of human perception. The question of what a work does to the viewer at the time of its reception is far more important than the question of the artistic intentions of the author and his time.

In cultural-historical retrospect, on the other hand, the linguistic structures inherent in pictorial artifacts represent the worldview of individuals and societies in the context of their time of origin. But here, too, form or function analysis is less relevant than discourse analysis, as called for by Michel Foucault in the sense of an “archaeology of knowledge“[17]as this places the history of ideas at the center of the work, which emancipates itself from the aspect of illustrating historical processes.

From the freedom of images to human freedom

The narrative power of the ideas brought to life creates, stabilizes, renews, destabilizes and destroys societies, a function that words and images have in common. The will to change only multiplies when it is given a representative form, a face or a voice. The self-image of individuals and societies is represented in the use of visual and written works.

The power of images has not increased in the digital age of the mass media of television, internet and smartphones, it has only changed. Iconoclasm is as old as the culture of images, as is the struggle for the sovereignty of interpretation of images or the attempt to monitor and control image production, image distribution and image use. Real-time images of collapsing dreams of the inviolability of Western claims to hegemonic power in a sea of dust, rubble and blood have radicalized the way we deal with the power of global flows of images. Since then, images of anger and retaliation have determined the quality of the conflict, multiplying in civil war scenarios around the world. This also reflects a discourse that is not about justice and freedom, but about revenge and vigilante justice.

Socrates justified his refusal to evade his own death through possible flight with respect for the law, the observance of which was more important to him than his life. His death, which included his unsuccessful attempt at persuasion by argument through free speech in court, was also his final legacy, with which he put the idea of the rule of law into practice.

It is not the fear of terror, but the de facto loss of control that images captured and disseminated via smartphones and the internet cause today that is triggering increasing surveillance, censorship, bans and persecution worldwide. Internet activists ensure the free flow of images by means of systemic interventions in global networks. Developers of open source products, operators of disclosure platforms, authors of countless blogs dedicated to the independent collection and dissemination of information stand alongside amateurs such as professional photographers, filmmakers and reporters who produce visual and written works and make them freely available online. It is not in museums and galleries, but in countless private homes and studios that the avant-garde of our time is at work, using the freedom of images to defend human freedom from heteronomy and surveillance.

From visual culture to cultural education

Works of art are not only powerful symbols, they also form, preserve and change reality. Only humans have the capacity to act. Images, on the other hand, visualize the motives for action, requests for action and instructions for action that people and society need for orientation in the environment. Evolution has ensured that humans perceive nature as a space for action that not only enables their species to survive, but also gives them the freedom to shape the conditions of their own existence. The use of this scope for action is evident in the cultural transformations of the natural space, in the images of the settlement areas, artifacts and performances. We can therefore only act coherently with our perceptions by following the motives, prompts and instructions of our pictorial works, as they form the externalized part of our brain that reflects the cultural evolution of our species in ideal and material form. Without the images of the cultural sphere, our species would fall back to the level of development of apes in a very short time, not because, according to Kant, words without images remain empty, but because analyses of fossil remains have shown that nothing has changed in the human genome for around 100,000 years.[18]

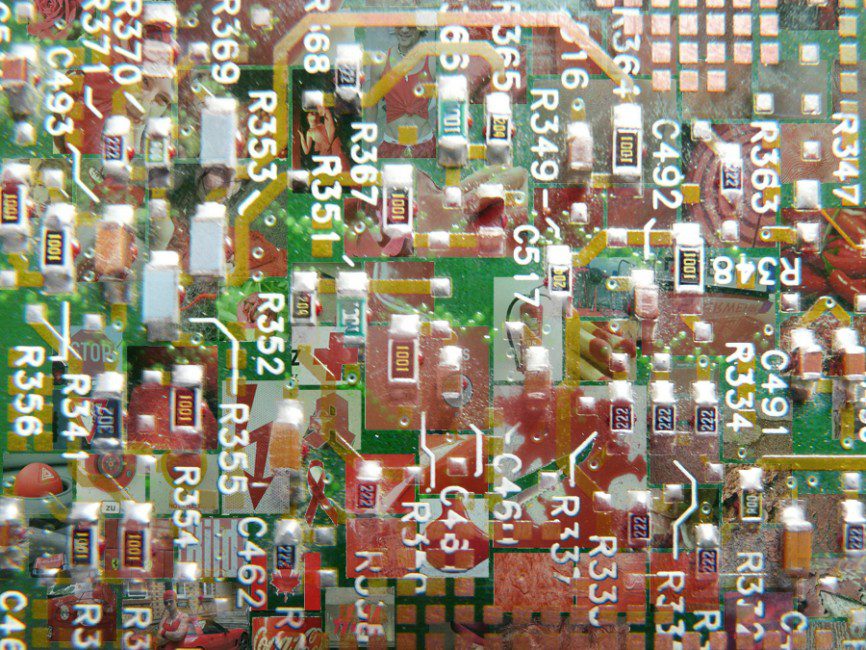

However, consciousness does not exist in the images, but exclusively in the self-perception and environmental perception of individuals. This subjective form of brain development and the development of reality is approached through interpersonal communication, creating an intersubjective form of consciousness that is represented in the form of a work. From a neurobiological point of view, works form interfaces between the brains of individuals who participate in the content presented and at the same time react to it through its reception. Works of art function like illustrative fixed points or nodes in a synaptic network of brains working in parallel. In terms of systems theory, Maturana and Luhmann’s concept of the[19] The concept of autopoiesis, which was coined in the course of the 20th century, comes into play here, as the purpose of pictorial works becomes different if one focuses not on the individual image but on the totality of all images. From this superordinate perspective, images serve exclusively communicative purposes, their production and reproduction is self-organizing and thus follows system-immanent functional contexts for the maintenance of communication. From the system perspective, the inner order of the images is not based on formal criteria, but solely in relation to the connectivity of the conceptually thematized content. This systemically necessary semiotic order of concepts is evident in language in the same way as in images. Nowhere is the common semiotic root of image and language more evident than in the system architecture of the Internet.

Participation and self-organization in the global flow of images

The possibilities for interactive searching, setting and linking of terms on the Internet, regardless of whether they refer to texts or images, are already leading to an explosive expansion, consolidation and networking of the virtual language and image space. Databases and programs such as image search engines, hypertext lexicons and social networks store, filter, organize, link and channel the infinite flow of images and texts, which today is causing profound changes in the way large parts of the world’s population perceive themselves and their environment. Since people’s ability to orient themselves and act is based on coherence between environmental perception and reality, the changes in the virtual world are reflected in society’s adaptation processes. Just 25 years after the invention of the World Wide Web (1989) and its language HTML(Hypertext Markup Language) by Tim Berners-Lee, it is hard to predict what the second Gutenberg revolution will mean for the creation, reception and handling of visual works.[20] It is already becoming apparent that the digital networking and participation of large parts of the world’s population in the creation and shaping of the flow of images is bringing about similarly far-reaching social changes as the cultural development and spread of print media. New digital trades such as web and software development or digital image processing, new design professions such as web design, interaction design, motion design(audiovisual media design), game design or interface design or new art disciplines such as media art, video art and digital art are expanding and changing analog fields of activity. Many other professions are in the process of being created and are generally boosting the rapidly growing cultural and creative industries, which are penetrating ever new areas of modern society. In Germany alone, 1.7 million people, from film producers to architects, are already working or are working on the virtual and real image of the world.

There are certainly justified reservations about the flood of digital images, in which the individual work of art hardly seems to have any validity, as the speed of image production is only surpassed by the expiry date of the novelties. At first glance, the creations of well-trained professionals and obsessive autodidacts are completely lost in the seemingly endless sea of amateur image producers, but this only highlights the need for excellently curated forums to exhibit outstanding digital images. On the other hand, anyone can become a curator on the Internet by commenting and integrating, which is why more and more exciting forums are forming that fish for innovative visual works online and share their catch with everyone. Once found, these collections become temporary sources of inspiration of great value, as the digital system does not invite you to return, but rather to a continuous search in which new and surprising discoveries and acquaintances can always be made.

The evolutionary benefits of images

While pessimistic media theories are concerned with the possibilities of rescuing the aura of the pictorial work from consumption in the mass media, such as the “iconic turn” called for by Gottfried Boehm, positivist media theories such as “communicology” emphasize the importance of the “iconicturn“. by Vilém Flusser emphasized the opportunities offered by the new media. Flusser sees the future of modern societies in their extensive medialization and networking, which dissolves existing authoritarian structures, introduces cybernetic or self-governing regulatory mechanisms and allows a comprehensive discourse in which the entire population participates. This brings us full circle to the self-image of Greek antiquity discussed at the beginning, in which works of thought were designed to maintain a discourse across generations, which makes them timelessly relevant to this day.

In antiquity, on the other hand, sculptures were viewed far more skeptically, as they were less an invitation to critical reflection than to quiet devotion, reverent amazement, or excessive amusement of the senses. At the beginning of the Enlightenment, Kant summarized these characteristics of the work of art once again under the term “disinterested pleasure“, a dramatically trivializing term in my opinion, which has shaped aesthetic education and debate right up to the present day. The fatal consequences are always evident where art, design and craftsmanship are turned into pleasing school activities and market-compliant services, whereby the factual power of images to perceive the world, think the world and change the world remains unused.

The most important aesthetic debate of our time is not about the competition between analog and digital media, which exist side by side and are mutually stimulating because they generate different perceptions, nor is it about questions of craftsmanship or technology, about authors, customers and markets, but about the discourse that a pictorial work carries into the world.

Conclusion: Dialogue between Socrates and Phaidros [21]

SOCRATES: And so it is, my dear Phaidros. But much more beautiful, I believe, is the earnest endeavor for these things, when one, applying the dialectical art, takes a suitable soul and with insight plants and sows speeches that are skillful in helping themselves and the planter and are not barren, but contain a seed from which other speeches grow in other souls, which are capable of preserving the same forever immortal and making the one who possesses them as happy as it is possible for a human being to be.

[1] Eco, Umberto: Essay “Opera Aperta” (“The Open Work of Art”) 1962

[2] Heidegger, Martin: “Der Urspung des Kunstwerks” in Holzwege, Klostermann; Edition: 8. 2003

[3] Joyce, James: Finnegans Wake, Wordsworth Editions 2012

[4] Plato: PHAIDROS. in Platon’s Werke, first group, first and second volumes, Stuttgart 1853 available at http://www.opera-platonis.de/Phaidros.html)

[5] Gegenfurtner, Karl R “Gehirn und Wahrnehmung”, Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag 2003, 2005, p.106

[6] Seel, Martin: Ästhetik des Erscheinens, Carl Hanser Verlag Munich 2003, p.17

[7] Aristotle: Rhetoric, Reclam Stuttgart 1999, 2007 edition, p. 19

[8] Baumgarten, Alexander Gottlieb: Aesthetica. 2 volumes. Kleyb, Frankfurt (Oder) 1750/1758

[9] Benjamin, Walter: Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit: Drei Studien zur Kunstsoziologie, Suhrkamp Verlag 1996 (published in 1936)

[10] Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix: A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Merve 2010 (published 1992)

[11] Vinci, Leonardo da: Trattato della pittura, Nabu Press 2011 (published around 1570)

[12] Heidegger, Martin: Being and Time, Max Niemeyer 1993 (published 1926)

[13] Böhme, Gernot: Atmosphere: Essays on New Aesthetics, Suhrkamp 2013 (published 1995)

[14] Damasio, Antonio R.: Descartes Irrtum, List Verlag Munich 1997 (published 1994)

[15] Kant, Immanuel: Critique of Pure Reason, Reclam 1986 (published 1787)

[16] Beckett, Samuel: Three Dialogues, Editions Rodopi B.V. 2003

[17] Foucault, Michel: Archaeology of Knowledge, Suhrkamp Verlag 1981 (Les Mots et les choses. Une archéologie des sciences humaines) was published in 1966)

[18] Hüther, Gerald; Krens, Inge “The secret of the first nine months”, Walter Verlag Düsseldorf 2005, p.20

[19] Maturana, Humberto R.: The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Cognition, Fischer 2012 (published 1987)

Luhmann, Niklas: Soziale Systeme: Grundriss einer allgemeinen Theorie, Suhrkamp Verlag 1987 (published 1984)

[20] Lee is currently working on ideas for a “semantic web” and for an “Internet of Things”, which should lead to a fusion of interface and utility object, of virtual and real space.

[21] Plato: PHAIDROS. in Platon’s Werke, first group, first and second volumes, Stuttgart 1853 available at http://www.opera-platonis.de/Phaidros.html)