Diploma sketchbook Burkhard Adam, Thinking with the pencil

What does Pandora’s box have in common with Burkhard Adam’s diploma project? Right at the beginning of the work, the “strong image” became a problem for the entire work process.

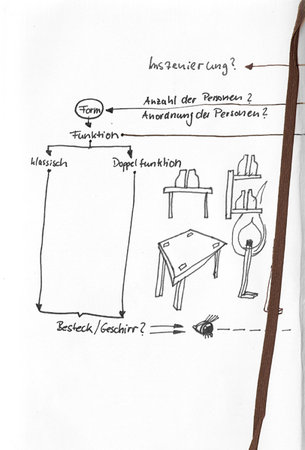

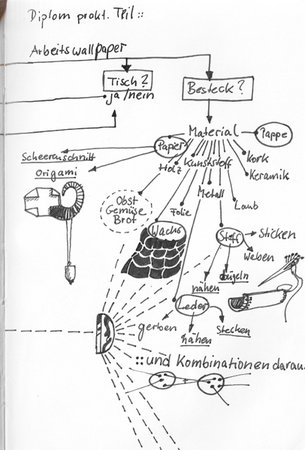

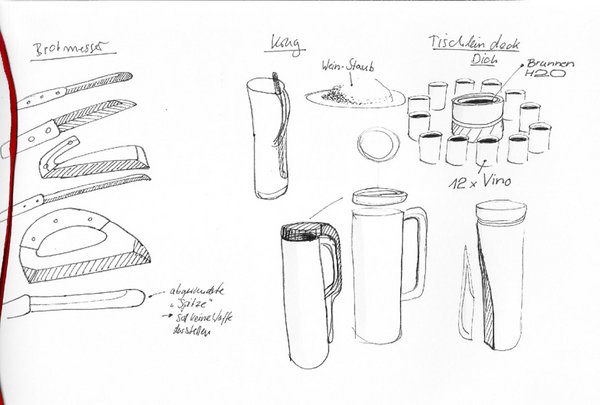

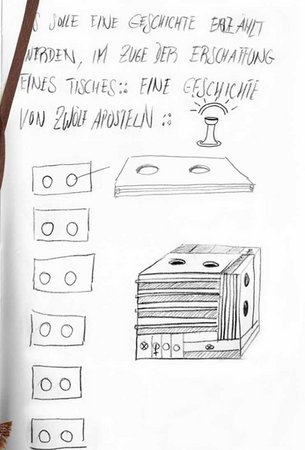

Everything was actually clear at the beginning. It was to be a table, a table at which different people could eat a meal together. This required various pieces of equipment, of which Burkhard already had a basic idea. The only thing left was the staging.

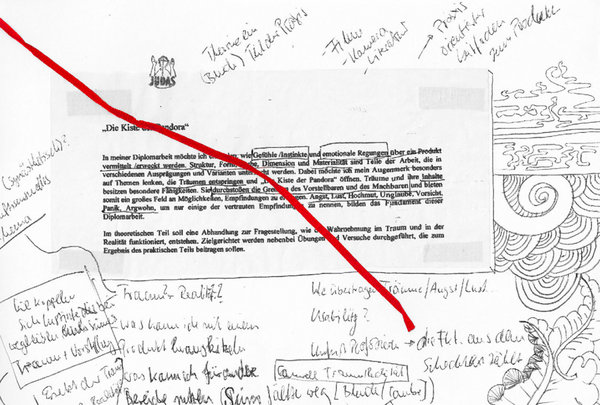

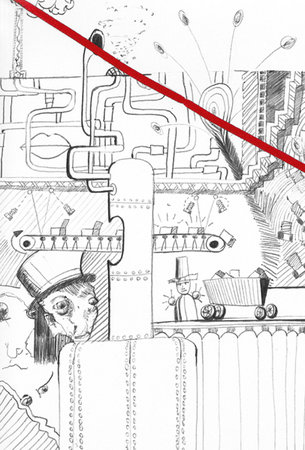

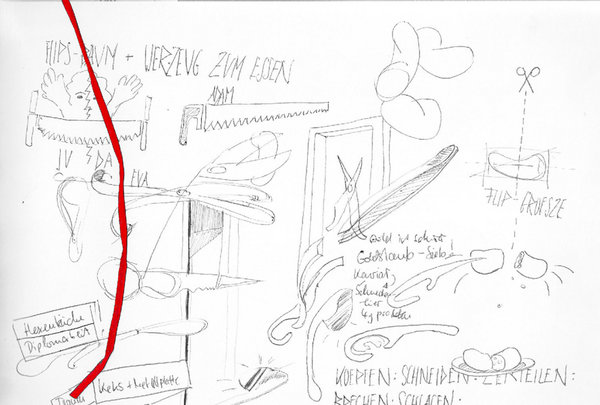

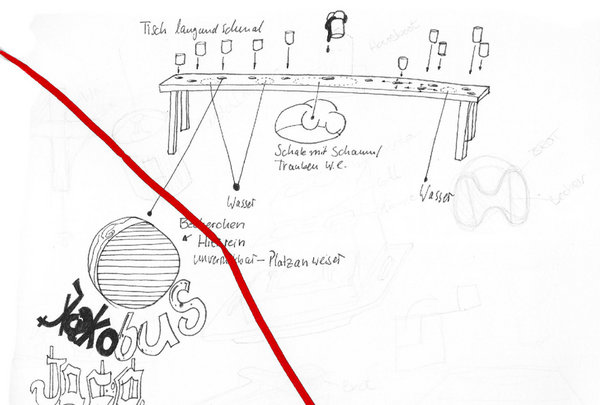

But there she was for the first time, the metaphor of Pandora, disrupting the process with her desire for a ritual. The simple question of the plot soon proved to be the biggest obstacle on the way to the goal. What should be served and in what way? What role do the guests have and what do the viewers do? Who should do what and why? Can it just be a table or does it have to be a special object? Will a normal knife do or is that too mundane? A jug for the wine, but what kind of jug meets the expectations of a minimalist meal? Wine and bread. The last meal. The Last Supper. There should be 12 guests. There must be a Judas. Water shall become wine. The table becomes a table. This is where the curse from Pandora’s box was revealed, the contents of which cannot be undone once they have escaped through the opening. In addition to old age and death, the “toil” of “work” also escaped the box, which from then on was an integral part of human existence and therefore did not spare Burkhard either.

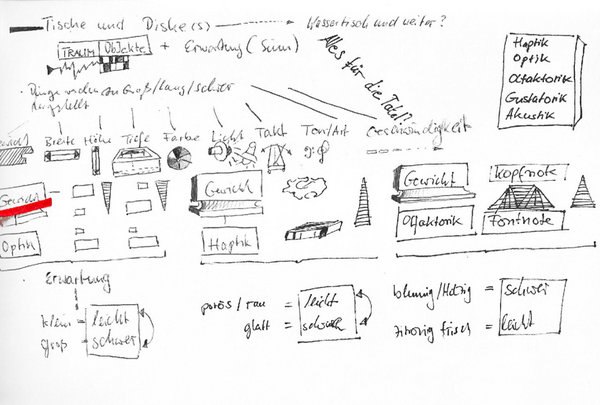

Around 2,700 years ago, Hesiod described Pandora’s box as a “beautiful evil”. Pandora was warned by the giver Zeus. The box and warning came to humans via Pandora. Curiosity alone drove them to act. Although people only took a brief look inside the box at first, this act was enough to release the plagues stored inside into the world. This was also the case for Burkhard. What began with curiosity soon became a burden. The further his aspirations grew towards heaven and the closer he tried to approach the divine, the more numerous and confused his thoughts became. What kind of table could carry this load, what kind of knife would it take to cut things that were beyond all comprehension? The guests, what to do with the guests! Everything suddenly seemed too mundane for the ritual. What ritual anyway? How do the guests get to the table? How do you pick them up and guide them to their seats or are they already there when you start? Where are the spectators? How long does it take to drink wine and eat bread? Is that even enough or do you need several gears? Does everyone take what they need or are the food and drinks served to everyone individually? Don’t we need more dramaturgical elements, light, sound, material? The more imaginative the thoughts, the less Burkhard brought to the discussions, until it came to the point where nothing more was possible, nothing more came.

The fantasy, the “beautiful evil”, had raised their own expectations to a level that paralyzed almost all activities. The world seemed to Burkhard to be a bleak place, filled with mundane things and pointless efforts. Why should you continue to invest work in it? Why should it be worthwhile to make something that nobody needs in the first place and that may already exist a thousand times? Don’t you want to change the world and society through your own creative actions instead of adding yet another, probably completely “superfluous” idea to the huge wealth of ideas? Imagination also includes doubt, the self-critical questioning of one’s own ideas. But even in the story of Pandora, the desolation did not last forever and the only possible way out for the people back then and Burkhard today was to take a second look in the box. Perhaps there was still something that could end her despair. And indeed. The second time, which lasted a little longer, “hope” suddenly and unexpectedly appeared at this point.

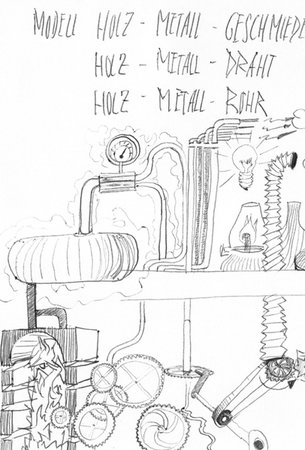

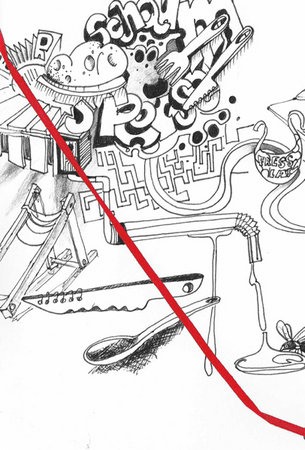

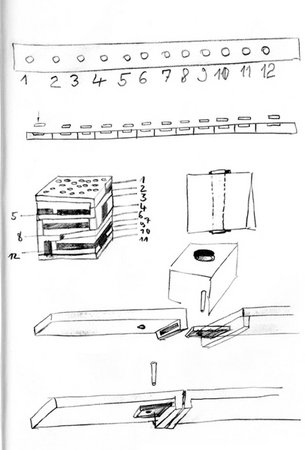

The solution lies in the problem! And so it was at precisely this point that Burkhard discovered the only way out of despair that a person has in such a case. The deed. Although the solution to his problem had been there from the start, he was only now able to recognize it. He immediately set to work. The first sketches and working models were created and variations emerged. His eyes lit up and his head cleared. Suddenly everything went very easily. There was a clear workflow and one step followed logically from the other. What makes things special? How do they lose their profanity and convey the world of ideas of their creators?

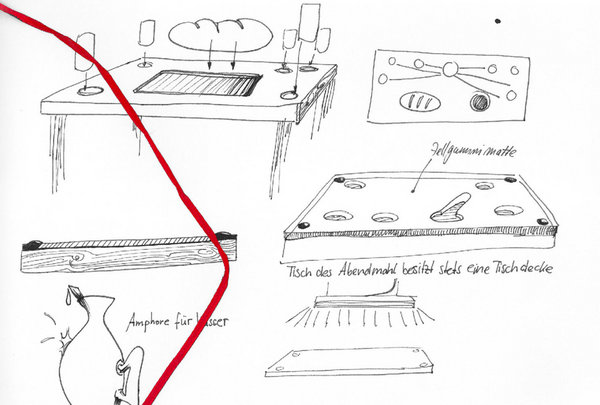

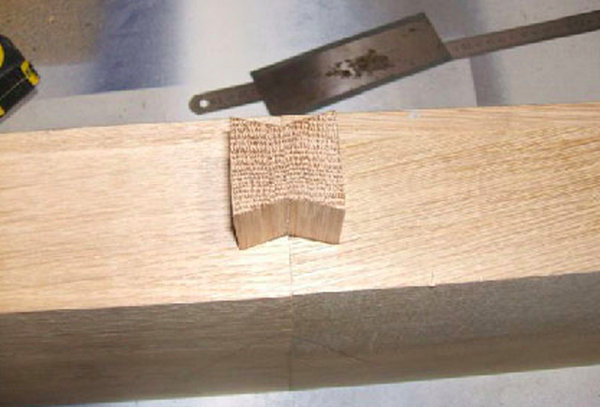

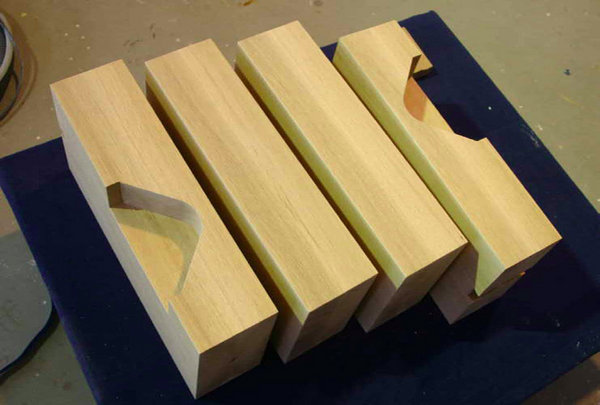

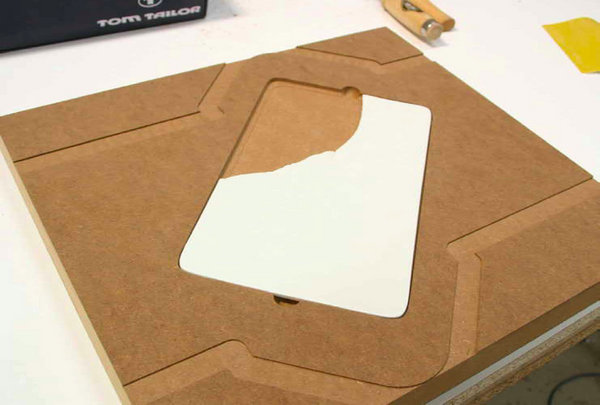

Burkhard began making his objects, his original idea becoming clearer with every blow of the forging hammer, every turn of the potter’s wheel, the firing of the porcelain, the construction of molds and the sawing, milling and assembling of the stained hard wood. The ritual of production is inherent in the objects created in this way and is visible to everyone. The celebration of the material, the constructions and their details creates reverence and respect for the achievement. Not a knife, but the knife, forged with countless strokes, heated to red heat and hardened in water, sharpened to extreme sharpness and marked with a specially devised embossing. It should be exactly this knife and no other. The same goes for the simple white ceramic plates, which fit flush into the recesses of the table, or the simple cups, whose rotational shape rises vertically from the surface. The slender shape’s height alone indicates the rite for which it is intended, over and above its functional purpose. Every ritual follows an inner order that is determined by gestures. Each object made by Burkhard demands a gesture, like the whole ritual.

The table is made from a solid, heavy wooden cube that can hardly be moved as a whole. Each piece is put in its place, taken out in front of the audience and assembled into a new unit. Not only the table, but each of its parts is unique. Finally, the mortised joints are stabilized with steel nails, whereby the sound of the hammer produced especially for this purpose evokes the idea of forging in the audience, who also become listeners. There it is again, the metaphor. Driving the nails through the flesh of the hands and feet into the wooden cross. Doubt and hope at the same time, Pandora’s legacy. Whenever you need to put your own ideas into practice in order to change the experience and behavior of other people, you have to open Pandora’s box again.

Workshop pictures Burkhard Adam and staging of the Last Supper (picture Matthias Ritzmann)